Few people know that the character of Indiana Jones, born from the imagination of George Lucas, is inspired by a man who really existed. Moreover an Italian. His name was Giovanni Battista Belzoni, from Padua, who lived between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. If Indiana Jones’s life seems adventurous to you, it’s because you haven’t read Belzoni’s memoirs.

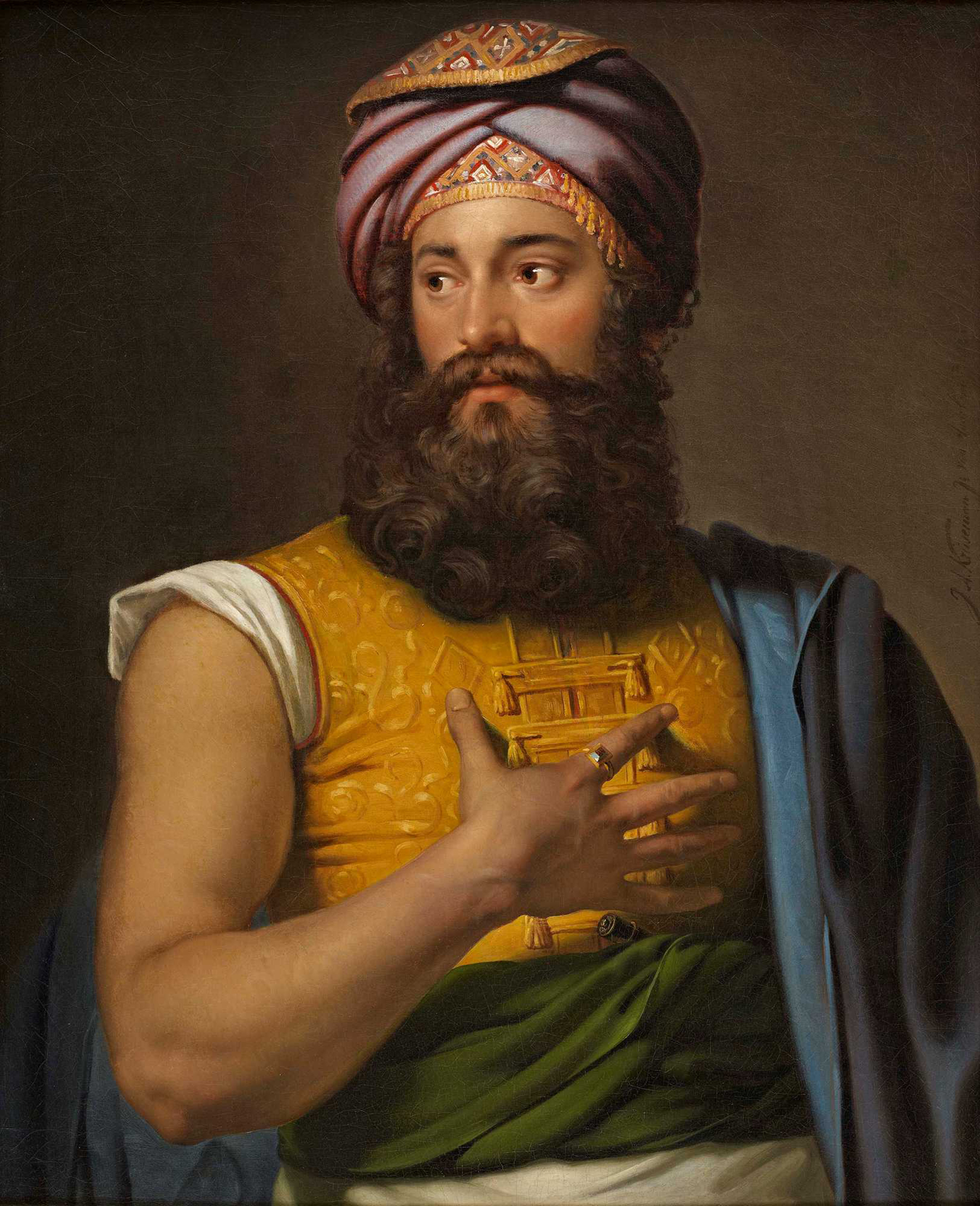

To the delight of enthusiasts, a new edition of Viaggi in Egitto and Nubia, published by Harmakis, has just been published (pages 190, € 16). The volume, written and published by Belzoni in 1820, after his definitive return from Egypt, and translated into various languages, obtained an extraordinary success and made him a man famous throughout the world. Even Tsar Alexander I received him in St. Petersburg giving him a precious topaz ring surrounded by twelve diamonds. Belzoni was an unusual individual from the outset. More than two meters tall, he possessed a prodigious force: he was able to lift ten men who had been placed on a support loaded on his shoulders. Handsome, self-confident, self-controlled, he possessed charm and charisma at will. As soon as he entered a room, people looked at him admiringly, as if subdued by his presence. The viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, a grim and ruthless man, was impressed by his respectful but casual manner.

Belzoni was born in 1778. As a boy he had assisted his father in his barber shop. At sixteen he moved to Rome to study hydraulic engineering: here he was passionate about archeology. But when Napoleon’s troops fell he had fled to the sly, also to avoid being drafted into the Armée. Having reached England in 1803 (a country he began to love almost as much as his native country), he married a young woman from Bristol, Sarah Banne. With the hopes of finding employment in the field of hydraulic engineering (in England the studies in that sector were at a much more advanced stage), he thought of exploiting his physical skills starting to perform in popular theaters like “Samson of Patagonia” before, and as a magician and magician then, between severed hands and women sawed in two. He also became famous for aquatic shows, complete with simulated naval battles. A period for which he later felt ashamed and tried in every way to forget (when someone reminded him of it he was furious).

But his life took a turn during his first trip to Egypt (at the time a province of the Ottoman Empire), after a brief stay in Malta. Once arrived in the land of the pharaohs, in Alexandria, with his wife and faithful Irish servant in tow, after a period of quarantine due to the plague that scourged the city, he came into contact with the circles linked to the British secret services, who thought they use him both as an informant and for the recovery of valuable archaeological finds located in high-risk areas. In those years, also thanks to the spectacular Napoleonic expedition in the land of the pyramids, with artists and scholars in tow, a fever blazed up for all that was Egyptian: the obelisks taken from the desert went to adorn the Parisian and London squares, and mummies, sarcophaguses and statues began to fill the halls of the main European museums.

Actually Belzoni had come to Egypt to build an innovative hydraulic machine for watering fields to sell to the viceroy, in the hope of producing them in series and getting rich. But some court officials had managed to wreck his projects by sabotaging the prototype, which had jammed right under Muhammad Ali Pascià’s implacable eyes.

Left penniless Belzoni had agreed to work for the British consul general, Sir Henry Salt. At that time a race was in progress between the French and the British for the possession of the most precious finds scattered in the various archaeological sites of the immense country. Soon between Belzoni, in the service of the British, and Bernardino Drovetti, general consul of France with solid relations at court, the rivalry reached its climax, and the two did not spare the low blows, even coming to the hands (needless to say who had the worst ). Belzoni was one of the few who dared venture along the Nile to Upper Egypt and even in Nubia, a wild and extremely dangerous land, inhabited by belligerent tribes, always at war with each other; the only one who has the guts to climb into dark and mephitic caves, and to venture along dark tunnels and sprinkled with human bones and skulls. During these expeditions, at the risk of his life (in several circumstances, armed with his inseparable guns, he had had to show strength and cold blood, defending himself against the rapaciousness of the local populations and the marauders of the desert), he managed to bring to light in the arch five years (from 1815 to 1819) finds of immense value, then transported to England and sold to the highest bidder, mostly at the British museum, where we can still admire them. The clashes with Drovetti (part of whose collection was sold in 1824 to the King of Sardinia, to then find a worthy place in the Egyptian Museum of Turin) became more and more frequent and violent, until it culminated in a process following which Belzoni was forced to leave Egypt forever (being able to count the rival on the support of the viceroy). The enmity between the two had become legendary. Drovetti, an explorer and art collector, a cultured man and gifted with great charm, had Piedmontese origins, but was closely linked to Napoleon; therefore after the definitive fall of the course he was recalled to his homeland but, refusing to obey, he ended up putting himself at the service of the viceroy of Egypt: returned to Piedmont many years later, he died at the age of 76 in Turin (according to some in a mental hospital ).

As for Belzoni, who became an expert in Egyptology, during his expeditions along the Nile he became the protagonist of extraordinary discoveries and discoveries. After succeeding in the task of transporting the colossal bust of Ramses II from Luxor (the ancient Thebes) to London (which at the time was thought to represent the mythological Ethiopian king Memnon, a descendant of the Trojan king Priamus), first, in 1817 , succeeded in penetrating the rupestrian temple of Abu Simbel, built in the 13th century a. C. by the pharaoh Ramses II and at the time of Belzoni considered inaccessible. The monumental temple, located in the current governorate of Aswan, on the shore of Lake Nasser, had been discovered four years earlier by the Swiss explorer and orientalist Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, who, having become a friend of the Italian, had encouraged and supported him in many of his exploits .

After having brought to light precious statues in Karnak and in the Valley of the kings (including an imposing statue of Amenofi III and the sarcophagus of Ramses III, sold to King Louis XVIII and now exhibited in the Louvre), Belzoni succeeded where many had failed, beating Drovetti over time who wanted to use explosives to break through: it was he who identified the entrance to the pyramid of Chefren, in Giza, in which, as he used to do, he affixed his showy signature (although it soon became clear that the pyramid had been violated six hundred years before by the Arabs). But his most important discovery was undoubtedly the discovery, in the Valley of the Kings, of the marvelous tomb of Pharaoh Seti I (father of Ramses II), entirely decorated with paintings and bas-reliefs in a blaze of colors, and still marked today as tomb Belzoni.

It seems incredible but all this was not enough to make him a rich man. Having often had to personally bear the costs of his expeditions (and perhaps not being cut out for business), from the sale of the numerous artifacts he conducted in Europe and from the success of his book, Belzoni barely got enough to pay off the debts accumulated over the years. Disappointed and discontented, also because he was snubbed by the academic world who judged him nothing more than an amateur and an adventurer, in 1823, after having stayed in Padua (which welcomed him as a hero), he decided to embark on a mad undertaking but, to his judgment, he would have handed him over to the legend: he would have left for the legendary Timbuktu, the city with the golden roofs, in Mali, and in search of the sources of the Niger river, despite the opposition of his wife (from Benin and Mali, yes he said, no explorer had ever returned. And in fact the fate was lurking: shortly after landing in Africa, in the Gulf of Benin, and having reached the river port of Gwato, Belzoni was assaulted by a violent fever and, after having tried to cure himself with opium and castor oil, he died of dysentery. Not before sipping a cup of tea and writing his last letter addressed to his wife (who for the first time refused to take with her despite the woman’s insistence). It was December 3, 1823. He was buried at the foot of a large tree, in a trench three meters deep, under a stone tombstone. Today there is no trace of the tombstone. And not even the tree is known anymore.